Cnidarian Walk

The word 'Cnidarians' is loosely translated as ‘stinging nettles’ in Greek.

A defining characteristic - among others - for a cnidarian is the presence of stinging cells - cnidocytes. This group of marine animals holds jellyfish, corals, sea anemones, sea fans, hydroids, to name a few. We’ll meet some of these creatures today.

Careful, not all cnidarians have a whopping stinger, but they can cause discomfort in varying degrees.

Ready?

Let’s go!

Pearly Sea Anemone

Scientific Name: Paracondylactis sinensis

Order: Actiniidae

Family: Actiniaria

Size: 5-6cm

Habitat preference: Sandy shore

Substrate: Sand

See this flower-like animal? Take a closer look, it’s beautiful, isn’t it? You’ll see the top, either closed off tight, or when under water, with its tentacles extended like the sun, around an oral disc. It catches food particles -- plankton, detritus, small particles in the water -- with these swaying tentacles and puts them into its mouth in the centre. They are also known to be opportunistic hunters of creatures that find themselves in its seemingly innocuous path, eating larger creatures and even fish, with an oral disc that can grow up to 6cm!

Named after the terrestrial anemone plant, sea anemones have a column, which looks a bit like a miniscule trunk, with which it lodges or attaches itself to a substrate - sandy or rocky. In many species, the column has a sticky disc at the base, helping moor the animal to the surface of choice.

You’ll usually see this particular species, the pearly sea anemone, like this - on the lower reaches of a shore. They prefer sandy or muddy patches and is the largest species seen in Mumbai.

Sea anemones are largely sessile, but some deeper-water species have been documented, swimming determinedly. In Mumbai, we have seen them thriving on sand, rock, driftwood, discarded boats, mudflats, and even some snail shells. They’re also beautifully coloured, below are a few photos of sea anemones.

It's common to see hermit crabs and small gastropods near Pearly sea anemones (Paracondylactis sinensis), but on this day we saw a tiny crab (perhaps a juvenile) going about its business under the much larger anemone.

Sea anemones move quite slowly so you would need to take a timelapse to effectively see how they move in their habitat.

A Pearly sea anemone (Paracondylactis sinensis) with its column partially above ground, at Juhu beach.

The sandy shores of Juhu and Girgaon are some of the best places to see these gorgeous animals.

A beautiful Pearly sea anemone at sunset.

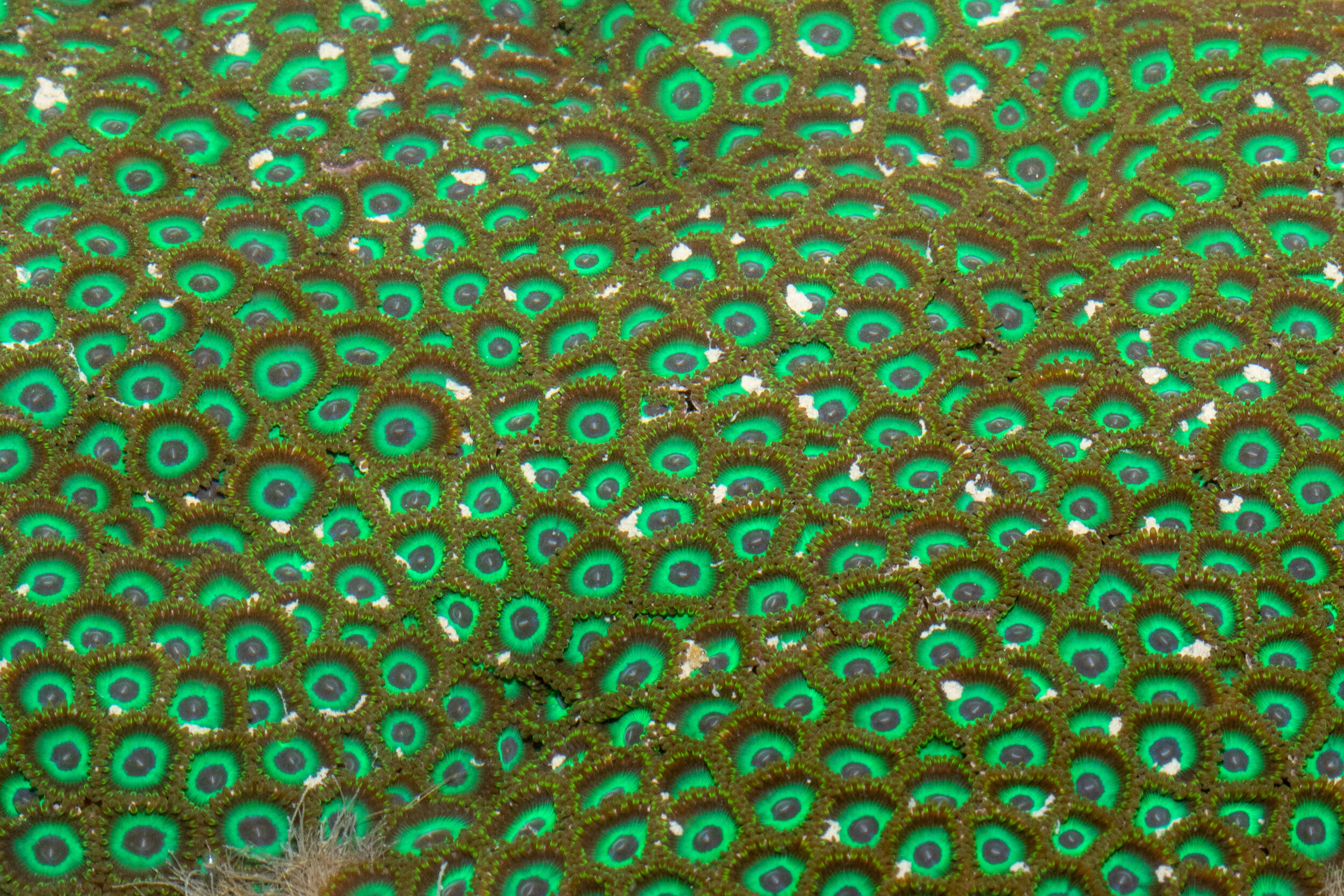

Zoantharians

A colony of violet zoanthids at Nepean Sea Road

Scientific Name: Palythoa mutuki & Zoanthus sansibaricus

Family: Zoanthidae

Order: Zoantharia

Habitat preference: Platform Rocky shores

Substrate: Silty Rock

Now you’re in for a treat. Walk along closer to the water’s edge on a rocky intertidal in Mumbai and chances are you’ll see these bright blue-green patches that seem to almost glow with colour.

A moment of silence for you to delight in these amazing cnidarians.

These are zoantharians, and you find them on only a few shores in Mumbai. These animals live in colonies and we have documented the presence of two species in Mumbai so far - Green button polyps (Palythoa mutuki) and Violet zoanthids (Zoanthus sansibaricus). Like anemones and coral, they attach themselves to a substrate, but unlike coral, their tissue is made (in some part) of chitin. You’ll see this kind of display only when it’s under water in a tide pool, otherwise, like the anemone, they stay shut, taking the colour of the silt around them, not revealing the bright colours they hold within. Micro-organisms which live inside the animals are called zooxanthellae. The polyp provides them shelter, and in turn, these microbes perform photosynthesis in sunlight, nourishing the polyp as well.

Violet Zoanthids react when disturbed by shutting, in this case by a hermit crab.

The green and brown form of the Green button polyp (Palythoa mutuki).

A Green button polyp (Palythoa mutuki) glowing under ultraviolet light.

A large colony of Violet zoanthids (Zoanthus sansibaricus) in close proximity to the sea facing skyscrapers of Nepean Sea Road.

Now, keep your distance and don’t touch them, because while they look glorious, some species have been documented to hold a poison called palytoxin. Research shows that this toxin is created not by the animal, but by the bacteria that live inside it. Large amounts of this have been known to paralyse humans.

Yes, step back, people.

Stick Hydroids

Scientific Name: Eudendrium sp.

Family: Eudendriidae

Order: Anthoathecata

Size: 2-5cm

Habitat preference: Rocky shores

Substrate: Under rocks

If you notice these deep tide pools, you’ll see some grass-like structures around the edges of the rocks. It’s easy to confuse these as grass, branching plants or algae, but even these are in fact animals. If you see these tentacles here, these help in the capture of food, which is then digested and shared with the rest of the colony.

Hydroids belong to the class Hydrozoa, meaning water animals (yes, in Greek again). In Mumbai we’ve observed different types of hydroids - some with feeding polyps and tentacles and some without. The former is armed with stingers that it uses to catch food and defend itself from predators (although many aeolid nudibranchs, which eat hydroids, are unaffected by their stingers).

A Cratena sea slug feeding on the polyps of a stick hydroid.

The open polyps can easily be mistaken for flowers.

The hydroids’ reproductive organs known as Gonophores look like tiny orange flowers.

Hermit crabs fighting while feeding on the hydroids.

Corals

Corals. Gather around, we'll show you both, soft coral and hard coral. When we first began our explorations of the intertidal zone in Mumbai, the only corals we knew of were sea fans and sea whips at Marine Drive.

These were introduced to the group by Pradip Patade, who is one of the founders of Marine Life of Mumbai. We’ve since sighted sea fans at a few more shores, where they play habitat to skeleton shrimps and cuttlefish eggs. Over time, we came across P and CE, which are widespread across the western seaboard. We sighted the snowflake coral from Haji Ali in 2020. Non-reef building corals usually seen in shallow water. Hard corals produce a skeleton formed of calcium carbonate. Each coral colony has tiny polyps that are tentacled and have a central disc with which they feed.

They are usually found attached to a substrate. We saw the False pillow coral at Haji Ali, in the upper region of the shore. Until then, we’d thought that these kind of corals only exist in the lower intertidal. Actually, until then we had mostly thought corals thrive only on pristine sandy shore, hardly on the rocky, crowded shores of Mumbai, where popular shores host hundreds of footfalls per day. This is probably why citizens are also delighted to come across them.

A colony of Snowflake coral (Carijoa sp.) on the Haji Ali rocky shore.

A Gorgonian sea fan (Pseudopterogorgia sp.) at Juhu.

Look closer and you'll realise that they're not all polyps. Here you can see the sea fan's polyps on the top and skeleton shrimps at the bottom.

A colony of False flowerpot corals (Bernardpora stutchburyi) at Backbay.

False pillow coral (Pseudosiderastrea tayamai) with the Haji Ali dargah in the background.

A small colony of False pillow coral (Pseudosiderastrea tayamai) at Haji Ali. In the background is the reclamation for the Coastal road project.

Seasonal Visitors

A porpita porpita in a tidepool

Keep a safe distance from this beauty because the tentacles of the Portuguese Man o’ War can deliver a whopper of a sting, sometimes warranting a trip to the hospital. The Porpita Porpita isn't quite so dangerous, but its tentacles will cause you discomfort just the same. The stunning purple, pink and blue tentacles in the Man o' War host large doses of stinging cells, and smaller protrusions make up the digestive organs.

In the monsoon, Mumbai welcomes these two wondrous species of cnidarians to its shores - Physalia physalis (the blue bottle or Portuguese Man o’ War,) and Porpita porpita (the blue button). Both are open-sea animals that are carried to the shores by seasonal winds and are stranded here;the tide carries some of them back in.

Keep a safe distance from this one as well because the tentacles of the Portuguese Man o’ War can deliver a whopper of a sting, sometimes warranting a trip to the hospital. The stunning purple, pink and blue tentacles host large batteries of stinging cells, and smaller protrusions near the top make up the digestive organs. The transparent gas chamber on the top is filled with part carbon monoxide and part atmospheric gases like oxygen, nitrogen and argon. This transparent chamber resembles an old Portuguese warship when on the water, giving the animal its name. The Porpita porpita, with its blue green tentacles and translucent white central disc, isn’t as venomous to humans but it’s still a good idea to observe these very fragile creatures from afar.

Porpita porpita arrives before the Man o’ war, small little colonies scattered over our beaches. Because that’s the amazing bit - when you look at both these creatures, you need to remember that every individual is actually made up of a colony of smaller beings which, unable to survive alone, come together to thrive as one.

It arrives every year like clockwork. This year, because of the Covid 19 lockdown, we were all indoors and these species had our open shores at their disposal.

A Blue button (Porpita porpita) waiting out the lowtide in a tidepool at Bandstand, Bandra.

Portuguese man o’ war (Physalia physalis) get their names from the shape of their floats, which some say resemble the sails of Portuguese warships of the past.

A macro closeup of Portuguese man o’ war (Physalia physalis) nematocysts (in yellow).

A top view of a Portuguese man o’ war (Physalia physalis).

We come to the end of our walk here; cnidarians are fascinating animals and we hope our observations made you love the city we share with them a little more.